Bazentin-le-Petit

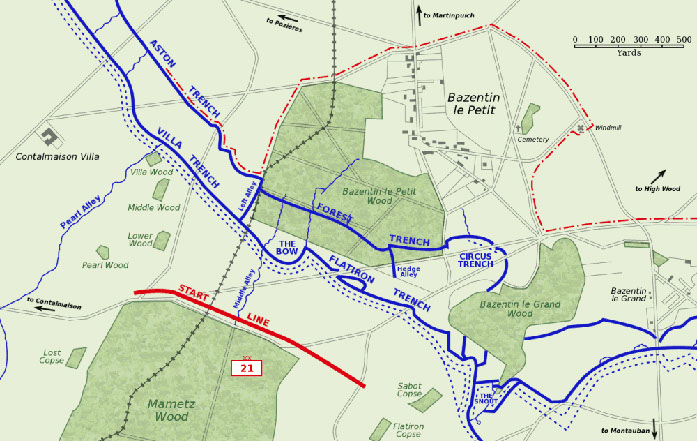

Map of the attacks in the area of Bazentin-le-Petit in July 1916.

Formation

Soon after the outbreak of war between Great Britain and Germany on 4 August 1914, Earl Kitchener, the Secretary of State for War, laid plans to raise a new army of 70 Infantry

Divisions. On 24 August, the Earl of Derby made the suggestion to Kitchener that men might be more willing to enlist in his new army if they could be assured of fighting alongside their own friends, neighbours and workmates.

Kitchener gave his blessing to the scheme, and sanctioned the raising by local councils, or even individuals, of what became known as ‘Pals’, or ‘ Commercial’ Battalions. These new battalions were aligned with existing city or county regiments, and in some large towns several battalions were formed as tram-drivers, cotton brokers, warehousemen and office clerks exchanged their uniforms, aprons and pinstriped suits for the khaki military uniforms, and took up the challenge of overthrowing the Kaiser and his vast armies which were then occupying Belgium and threatening to conquer France. The war, it was thought at the time, would be over by Christmas', and nobody wanted to miss out on the action. The novelty of exchanging a work bench or office desk for the thrill of serving one's King and country was too much to resist, and young men by the thousands enlisted to serve in the ‘Pals’ Battalions. Uncontrolled patriotism guaranteed the success of Kitchener's scheme, and intercommunity rivalry led to towns and county districts seeking to recruit more ‘Pals’ than their neighbours. The raising of the Preston ‘Pals’ was the idea of Mr. Cyril Cartmell, son of the Mayor of Preston, Councillor (later Sir) Harry Cartmell. On 31 August 1914, Cyril Cartmell placed the following advertisement in The Lancashire Daily Post:

Kitchener gave his blessing to the scheme, and sanctioned the raising by local councils, or even individuals, of what became known as ‘Pals’, or ‘ Commercial’ Battalions. These new battalions were aligned with existing city or county regiments, and in some large towns several battalions were formed as tram-drivers, cotton brokers, warehousemen and office clerks exchanged their uniforms, aprons and pinstriped suits for the khaki military uniforms, and took up the challenge of overthrowing the Kaiser and his vast armies which were then occupying Belgium and threatening to conquer France. The war, it was thought at the time, would be over by Christmas', and nobody wanted to miss out on the action. The novelty of exchanging a work bench or office desk for the thrill of serving one's King and country was too much to resist, and young men by the thousands enlisted to serve in the ‘Pals’ Battalions. Uncontrolled patriotism guaranteed the success of Kitchener's scheme, and intercommunity rivalry led to towns and county districts seeking to recruit more ‘Pals’ than their neighbours. The raising of the Preston ‘Pals’ was the idea of Mr. Cyril Cartmell, son of the Mayor of Preston, Councillor (later Sir) Harry Cartmell. On 31 August 1914, Cyril Cartmell placed the following advertisement in The Lancashire Daily Post:

Recruitment on the flag market, August 1914

‘It is proposed to form a Company of young businessmen, clerks, etc., to be drawn from Preston and the surrounding districts, and be attached, if practicable, to a battalion of the Loyal North Lancashire Regiment. Will those who would like to join apply here any afternoon or evening this week – the earlier the better. Town Hall, Preston Cyril Cartmell 31st August, 1914’

Within two days 221 local men had volunteered for service, and the ‘Preston Businessmen and Clerks’ Company’ of the 7th (Service) Battalion, Loyal North Lancashire Regiment was formed.Three other companies making up the battalion were filled by ‘Pals’ from Blackpool, Kirkham and the Fylde, and Chorley. The men were medically examined at the Public Hall, and on Monday 7 September the ‘Pals’ paraded before an enthusiastic and patriotic crowd in the Market Place before marching along Fishergate to the railway station and leaving the town for their training.

Within less than a week, the young men in the Preston ‘Pals’ Battalion had left office desks and warehouses in Preston to become part of Kitchener’s new army which was due to leave Preston on 7 September 1914.

Unique photograph of Preston Station as it was at the time of the Pals departure

Raising a vast army of 70 Infantry Divisions (well over one-and-a-quarter million men in 1914) is something which can be done in a few weeks; but equipping and training it to meet a ruthless and highly-professional enemy is a different matter. Kitchener and the British commanders were in no doubt that it would take twelve months, possibly much longer, before the ‘Pals’ Battalions could be expected to take their place alongside regular and territorial troops. The Preston ‘Pals’ did their training at Tidworth, Bulford and Swindon before crossing over to Boulogne on 17 July 1915. Once in France, training for trench warfare and gas attacks

continued for a further two months. In September 1915, exactly twelve months after their formation, the Preston ‘Pals’ took a minor part in the Battle of Loos, and received their first casualties.

The dreadful reality of the war had already been made clear to local people as the Preston Guardian and Lancashire Daily Post reported the losses of Preston men, many of whom had fought with regulars and territorials during the early months of the war. To these names were now added a small number of Preston Pals, who had been charged with holding the line at Laventie near Loos.

The soldier’s obituary was usually accompanied by details of his school and church associations, the firm he worked for before enlistment, and the football or cricket teams he had played with. Everybody knew these lads, and personal family grief was combined with a more general local sympathy because the men had fought under the particular identity of the town. To understand the Battle of the Somme, fought in the district east of Albert and south of Arras, one must first understand the position of the contesting armies on the Western Front in 1916. Following the opening battles soon after the outbreak of war, both the Allies and the Germans found themselves firmly lodged in a deadlock of trench warfare. Long lines of trenches stretched across France and Flanders from the Swiss border to the Channel coast. Allied attempts to break through in 1915 had failed, largely because of the shortage of men and ammunition. Everything, it was confidently forecast, would change in the summer of 1916. By that time, Kitchener’s new army would be in France in great numbers – the ‘Big Push’ would be underway, and soon the defeated Germans would be back in their homeland. Following a massive seven-day artillery bombardment, 18 British Infantry Divisions attacked the Germans along a 15-mile front on the morning of 1 July 1916. The troops, many of them consisting of ‘Pals’ Battalions, were convinced that it would be a ‘walk-over’. Never had Britain put such a vast army into the field; never had such a patriotic force faced a battle with such confidence. Yet, within minutes of coming out of their trenches, the ‘Pals’ Battalions walked into a hail of machine-gun and sniper fire. The dead lay strewn across No Man’s Land as many British soldiers failed to advance even a few yards from their own lines. By nightfall on the 1 July 1916, the British Army had suffered 60,000 casualties, one-third of them killed. Within a few days, news of the Somme disaster was obvious in Britain as whole communities received notification of the local men who had been killed, wounded or captured in the battle. In some small towns, every family was touched by the tragedy.

Husbands, sons, brothers and nephews had fallen in action, and newspapers carried page after page of photographs of ‘Pals’ who had made the ultimate sacrifice. The town of Accrington, for instance,

learnt the sad news that 235 officers and men had been killed, and at least another 350 wounded, within the short space of twenty minutes. These men had belonged to the Accrington and Blackburn ‘Pals’ who formed the 11th Battalion of the East Lancashire Regiment. However, there were spectacular successes in the south of the battlefield where all objectives were captured at Montauban and Mametz, with Fricourt falling the following day and it was upon these gains that the British Army would now found its future strategy.

The 7th Battalion of the Loyal North Lancashire Regiment was in the Order of Battle for the first day of the Somme. The battalion was to take part in an assault against the German lines in late afternoon, but, by this time, the complete failure of the earlier fighting brought about a cancellation of further attacks that day. The Preston ‘Pals’ were in reserve to the 25th Infantry Brigade and so escaped the horror of the 1 July 1916, with the 7th Battalion suffering only 25 casualties.

Non-Commissioned officers and men of the Loyal North Lancs regiment in the trenches

The Pals were moved into the front line at La Boisselle on 3rd July to strengthen the position. From here the 19th Division would capture the village on 6th July after very heavy fighting. The Pals were then moved into reserve. From their reserve positions in Henencourt Wood, the Preston Pals were moved with the 7th Bn LNL to Bazentin-le-Petit, with hot tea provided on the way at Fricourt. After the heavy fighting on July 23rd, they rested in Mametz Wood before being relieved on 31st July. From there, they moved north to Flanders and returned to the Somme in October. When the Somme offensive closed, there had been over one million casualties, British, French and German.

By the time the Battle of the Somme ended, in mid-November 1916, the identity of the 7th Battalion LNL had become somewhat diluted. Many of the original ‘Pals’ had been commissioned or had joined other units and casualties had been replaced by new drafts from Britain. After the Battle of the Somme, what remained of many other ‘Pals’ Battalions were reformed with men who came from differing residential districts. No way was the Government going to allow another disaster of Somme proportions to provide particular towns and districts with news of such heavy losses in a comparatively short space of time. In any event, compulsory military service had been introduced in 1916, and no longer was it necessary to encourage recruitment by offering service inducements to volunteers. The battalion was officially disbanded in February 1918 It would be outside the scope of this article to give complete details of the Preston ‘Pals’ losses and record of service in France, but a few names and facts help to give us a guide to the character of the men who formed the Company. The first officer to be killed in action, in February, 1916, was Lieutenant Maurice Bannister, son of the vicar of St George’s Church; and another well-known Preston father who lost his son was Alderman Hugh Rain (Will Onda, the cinema proprietor),

Corporal Frank Wood, of Connaught Road, Broadgate, was the first member of Orchard Methodist Church to become a casualty in the war. He had formerly worked for Merigold Brothers in the Old Vicarage. Lieutenant Harold Fazackerly, of Ashton, won the Military Cross and Bar before being killed in action in August, 1916; and Lieutenant Horace J. Lancaster, of Penwortham, also won the Military Cross.

One of the last, quite possibly the last, surviving members of the Preston ‘Pals’, who served in France was James Collier Nickeas. He died in 1986, in a Barrow hospital, aged 93. His father once ran the ‘Alexandra’ ballroom and cinema in Walker Street, Preston.

The Preston Pals were a group of men from the Preston area in Lancashire, who volunteered to fight during the First World War. In the autumn of 1914, volunteers from all over the country represented the flower of British youth who were willing to fight for their country.

After the campaigns of 1915 and the Battle of the Somme the following year, their deeds were written in blood across the battlefields of France.

The Preston Pals later fought with distinction at Messines Ridge in Belgium in 1917.

Departure

You can give your support by making a small donation to help with the Memorial Insurance and maintenance.

Please send a cheque made payable to Preston Pals War Memorial Trust by downloading a subscription form HERE and print out and send to us with your kind donation or set up a regular giving amount by standing order, please contact us HERE

Registered Charity No. 1141064

website by Northern Studios